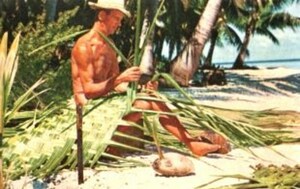

Solitude and Contentment

Lessons from hermit lives

In the past two months, we visited modern hermits and ancient Chinese classics, read about Going Slow and about Homelessness and Heimat and the Rhetoric of Refuge. There are still so many topics we haven’t touched, so I might keep putting up articles on hermits onto these pages. If you are interested, subscribe so you don’t miss any post!

Now the time has come to wrap all this up. What was it good for? Is there anything hermits can teach us normal people of today about how to have happier and more fulfilled lives?

Hermits, alienation and empowerment

Interestingly, only a fraction of hermits in history and present are religious hermits. There certainly is a number of Christian hermits (and this was a big movement in the times of the Desert Fathers), and today we still have Daoist hermits in the Zhongnan Mountains in China and elsewhere (more on those in a future article). But many hermits today are secular hermits. People who leave our hectic, capitalist world in order to seek a quieter, more meaningful life, without the pressures, expectations and prescriptions of organised society.

It is undeniable that every human society needs the individual to conform to some common understanding of what the limits of their freedom are. We trade freedom for safety, if we are lucky. By submitting to society, by giving up a part of our freedoms, we gain the support and the help of society in terms of financial security, healthcare, childcare, infrastructure, ease of life, and many other things.

This trade-off is a continuum: The hermit is at the one end, free like a wild animal but relying entirely on him- or herself for survival; the corporate employee on a lifelong post is at the other, having traded freedom for safety and a retirement scheme.

Much less obvious are other ways how we trade away our freedom. Many philosophers, from Epicurus and Bertrand Russell to Erich Fromm and Richard Taylor (whom we have all discussed previously in these pages) emphasise how we lose our freedom by accepting society’s values and ideals. By blindly embracing the desires that society prescribes, we let others take control of our lives. Epicurus speaks of “vain desires,” Erich Fromm of the failed promise of 20th century capitalism, and Richard Taylor even says that a person who only follows the lead of others loses a crucial part of their humanity and becomes a non-person.

Richard Taylor (1919–2003) thought that it’s creativity that makes us feel happy and fulfilled. According to Taylor, a life lived without exercising one’s creativity is a wasted life.

If alienation is the process of becoming estranged from one’s daily activities, then the hermit’s life is the opposite of alienation. The hermit in her hut becomes the master of her own life, only accountable to nature and to herself for her decisions and choices. In the hermit’s hut, every activity is aligned with the imperatives of one’s survival. The hermit does not need to ask for the meaning of her daily actions. Bringing water up from a stream, tending to a garden, feeding a few chickens or a goat, repairing the hut’s leaking roof: these actions are immediately and obviously meaningful, and the beneficiary of one’s life is only oneself, rather than some nameless corporate entity.

With this comes the feeling of empowerment. We are perhaps not always consciously aware of how dependent we are on society for even our bare survival; but somewhere deep inside we feel that we have no real power over our fate. One could see all sorts of irrational behaviours, from vaccination and global warming denialism to gun worship, conspiracy theories and the “prepper” culture as expressions of that longing of modern citizens for more control over their lives. Refusing a vaccination is an (ultimately mistaken and empty) gesture of empowerment, a misguided attempt to take back control over one’s body. Storming the US Capitol could be interpreted as a misguided attempt of taking back control over one’s social contract. And carrying a gun is a futile gesture of personal empowerment, an attempt to deny one’s fundamental powerlessness in modern society.

The hermit does not need any of these symbolic gestures, and in this she might even be a model to us non-hermits. Hermits are in control of their lives at every moment. And although we cannot fully live hermit lives within society (and probably wouldn’t want to), we can try to improve our basic survival skills, we can try to take back some control over the everyday mechanics of our lives. For some of us, the pandemic has provided this opportunity to separate ourselves from the endless chatter of our social surroundings and to experience just a little bit of the peace, quiet and self-determination of the hermit.

The philosophy of Karl Marx (1818-1883) has been hugely influential throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. One of his best known concepts is the idea of “alienation” that describes how, in capitalist societies, human beings get estranged from their work and from themselves because of the way the production of goods is organised.

For the philosopher Immanuel Kant, autonomy, self-determination, is the defining characteristic of being human. Even the Biblical story of the Garden of Eden and the Fall of Man could be read as a parable of empowerment: life in the Garden of Eden is easy, protected, regulated, free of effort, labour and sin: a paradise. But man is not made for such a life. In a gesture of empowerment, Adam and Eve take control of their fates: they exercise their human autonomy and are, consequently, thrown into a world of sweat, pain, hunger and sin. But it is now a human world, and by losing the perfection of paradise, humans have gained something else: the ability and the power to make their own decisions.

Perhaps the hermit is, after all, an example, a manifestation of that ultimate human freedom and autonomy.

The value of being alone

Another aspect common to all hermits is solitude and alone-ness, which is not always the same as loneliness. In fact, very few hermits complain of loneliness and many are quite social, although always in small doses around that fundamental solitude that forms the core of their lives.

Solitude provides us with a space in which we can be quiet and still and in which we can explore our own selves without being ceaselessly distracted by the world outside. Many hermits have talked and written about how solitude and the observation of their own minds in silent meditation led them to a better, deeper understanding of their selves (for example Jane Dobisz).

The strength that comes from being alone and quiet for a period of training, from being able to listen to one’s inner voices and visions, has been a feature of spiritual tales from the terrifying meditation visions of the Desert Fathers and Tibetan sages to Luke Skywalker’s realisation of his true self before seizing the power of the Force in Star Wars.

And perhaps this is something that solitude can also do for us, in our hectic everyday lives. It’s worth at least trying to switch off TV and Internet for a few evenings; to retreat into a corner and just be with oneself for a while, without speaking or reading, without listening to music, without talking, without any distraction.

In her honest and entertaining book “One Hundred Days of Solitude: Losing Myself and Finding Grace on a Zen Retreat,” Zen teacher Jane Dobisz recalls the three months she spent as a young person alone in a hut in the woods, bowing, chanting and meditating.

Saving the Earth

Finally, one very important skill that we can learn from most hermits is how to live in a way that is more sustainable and less suicidal than our usual, consumerist life. Hermits, from necessity, have to recycle everything. Since they have little contact with society, they also have little access to industrial products, fuels, plastics; and little use for things that are usable only once and then thrown away.

Hermits, in this way, might be seen as models of how we could all improve our lives and our chances of survival as humanity, by reducing our footprint on Earth. Hermits emit less, consume less, create less garbage and grow most of the resources they use locally and by themselves.

In the run-up to COP26, there is perhaps no better time to study the lives and everyday practices of people who manage to be happy and to live fulfilling lives entirely outside the global systems of exploitation and destruction.

◊ ◊ ◊

Thanks for reading! If you liked this, feel free to subscribe and comment below! Cover image by He Zixiang on Unsplash.