Human Dignity and Freedom

Why restaurant menus may be destroying humanity

I live with my family in Hong Kong. Our holidays we spend in Greece. Eating in a restaurant couldn’t be more different in the two places.

But is there perhaps more to it than just a superficial difference? Might it be that the way we order food shows us something deeper, more fundamental about the human condition? Might it be that our very dignity as human beings is reflected in the way we talk to a restaurant waiter? – Let me explain.

Restaurant orders, dignity and freedom

In Greece, when you go to a local village restaurant, you’re often taken to the kitchen to see the available dishes. Sometimes these will be ready-made and you just point at a pot and get that thing. But sometimes, you will also just see components of food: french fries, tomatoes, cucumbers, pieces of meat, various small fish, pasta or rice, meatballs, and an array of appetisers. If you know the owner of the tavern well, he might produce additional dishes from the back of the kitchen, the best bits, kept only for his family and friends. And you will look around, look at this and that, ask a few questions about what is fresh and what’s only for the tourists, and then you’d order: a bit of this, but with the sauce from over there, a spoonful of that there, but on one plate with this, and the salad made of this ingredient and that, but leave out the third thing and replace it with something else that you fancy.

Later, when you go out and look at the other guests' tables, you will see that everyone’s menu is as individual as their fingerprint, reflecting not only their tastes and dislikes but also their standing with the owner of the shop and his family. Every collection of dishes, every order of drinks is the result of a deeply personal history, of a number of choices and constraints that determine the particular configuration of dishes on every table.

It’s all very different in Hong Kong, and, I guess, in most other capitals of the so-called developed world. Here, you go into a restaurant where you are kept as far away from the kitchen as possible. The food processing area is off-limits to the guests. You order, not according to your taste, but following a rigid menu. You want dish 13 or 28, and that’s it, as far as choice is concerned. You’d like 28 but with the salad that goes with 13? Sorry, we don’t understand that order, that’s not in the menu, it’s not in the computer, and even if we could make it, somehow, we wouldn’t know how to charge you for it, or how to explain it to the computer system that processes the orders and that manages the inventory and supplies. You can’t have this, and that’s the end of it.

The cheaper and more popular the restaurant, the more mechanised it is, the more prominent the atomic choices on the menu become, the less freedom the customer is permitted. A McDonalds order consists of just pointing at photographs of the food. There is no space for even the choice of how fried the fries should be, or that one would like a bit more or less of that salad sauce. You get one pack of it and that’s it. Shut up, eat, and leave us alone.

What is mechanised in these places is not only the restaurant but also and primarily the customer.

Human autonomy

For the philosopher Immanuel Kant, the very essence of what makes us human is our <em>autonomy</em>. For Kant, this means: our essential freedom to choose how to live our lives. Of all things in nature, of all animals, only human beings have autonomy. Only we are able to transcend our instincts, to tame our natural, built-in behaviour, and to act instead following our rationality and our own choices about what we consider valuable and good.

This freedom is even stronger than our instinct to live. People have sacrificed their lives for a political cause. Many have died in prisons as a result of hunger strikes. A hunger strike is an affirmation of this very human, this essential freedom that only we have: no hungry animal can refuse to eat and instead opt to starve itself to death. We can. For Kant, this is the basis of our dignity as human beings, of our unique, immeasurable value.

For Kant, it is the freedom of choice that makes us human. Nothing else.

Back to the restaurants. When we accept that our essential, defining freedom is subordinate to some menu that someone has made and that we have to follow; when we assent to give away our autonomy to an institution in exchange for a burger with fries; then we have essentially abandoned our humanity and our creativity, we have become a part of the machine, a little cog in that vast machinery that is McDonalds or any other restaurant, every shop, every institution.

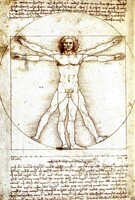

Even universities work like that, and this is tragic. Why can students not study a little bit of this and a little bit of that? Why do we think that the only valuable education is that which fits into a pre-defined catalogue of menu choices: doctor, engineer, accountant? The best minds of the past have always been those who weren’t restricted in their freedom. Doctors who studied religion and philosophy, like Albert Schweitzer; artists who knew about engineering, like Leonardo da Vinci; philosophers who were also physicists, like Archimedes; poets who became presidents, like Vaclav Havel; architects who became novelists, like the German Nobel nominee Max Frisch.

What is more precious than one’s access to knowledge, one’s essential creativity, of which arise endless benefits to society and the world? And we treat this, nowadays, in the same way as we restrict the choices of a burger order at McDonalds.

Capitalism and the loss of autonomy

Why do we let society take away our human freedom? Why does it even want to?

Erich Fromm, psychologist and philosopher, points out that the capitalist system of production needs us to be compatible, standardised, interchangeable human units. In a factory setting, it doesn’t matter if a worker is also a poet or a painter. In fact, it would be a distraction. The best worker is one who has no option but to work. One who cannot turn away, who cannot choose another life, because he has never been offered one, and because he has not developed the talents, the creativity and the autonomy that would make it possible for him to choose and to pursue a better, richer, freer life. Our system of production needs us to be impoverished, to be humans fulfilling the minimum standard of what is required, so that we can stand at the assembly line and assist the machines that produce our goods.

The same is true of us as consumers. The system of consumption that we have installed in our societies needs us to have a uniform taste; because only a uniform taste for goods can be optimally satisfied by the mass production of goods that our factories spit out. Imagine if nobody fell for the dictatorship of fashion, if nobody listened to ads, if nobody desired to have the same stuff as the influencers on Instagram or Facebook: much of our capitalist system would collapse. This system is not compatible with free, creative, truly individual human beings, individuals who each have their own values, thoughts, preferences and taste.

The system of cheap goods we have created needs us to be mindless, standardised consumers of just these goods.

Another world of dignity and freedom

So is there a way out of this? Can we reclaim our individuality, the divine spark of our creativity, our essential uniqueness, our moral autonomy and freedom?

There is.

Richard Taylor (1919-2003), philosophy professor at Brown and Rochester, says that we must make an effort, every day, to live our lives in the most creative way possible. When you go to a restaurant, don’t follow the menu. Don’t assent to being a remote-controlled slave of whoever wrote that blasted thing. Choose your own food, and demand that it be brought to you. If this doesn’t work, order two dishes together with a friend and mix them up on the table. When you go for a holiday, don’t take the 5-countries-in-7-days package, photo-op at the pyramids included. Learn the language, get a map, and do your own travelling.

This has nothing to do with convenience but everything with being, and defending, what is essentially human: our freedom, our autonomy, the divine spark that was entrusted to us when we emerged on this planet as the only beings that could really choose how to live their own lives.

It is a moral obligation to honour one’s humanity.

And so, yes, that restaurant where I can walk into the kitchen and put my own dishes together – it does have something to do with philosophy after all. Eating is never just eating, and studying is never just studying. With every choice we make, we create a different world for ourselves and our children: Either one that respects our humanity, or one that seeks to abolish it.

It’s our choice, still.

Your ad-blocker ate the form? Just click here to subscribe!

Thanks for reading! Photo by Igor Ovsyannykov from Pexels