Robert Rodriguez on Hermits

Philosopher interviews

Thank you! Thanks for your kind words. The Hermitary website is entirely my effort, since its inception in 2002. From the outset I used a pseudonym, and only use my real name now that I am launching a book, The Book of Hermits. I was born in the United States. My ancestry is partly Caribbean (Puerto Rico and Cuba) and partly Spain (specifically Asturias). I pursued history and philosophy at university and became a librarian in universities and colleges for some forty years until retiring. I identify with the Spanish writer Azorín’s self-description of being a pequeño filósofo, a minor, or insignificant, philosopher.

My wife and I married nearly fifty years ago. As the poet Rilke said, “Love consists of this: two solitudes that meet, protect and greet each other.” I also like the story of the ancient Chinese couple Meng Guang and Li Hong, who reclused to the mountains together. Meng Guang was an exemplary woman who prodded her husband to reclusion, and the Tang poet Po Chū-i praised his own wife as “my Meng Guang.” We live in a tiny house among mountains and forests in Vermont. We have two adult sons.

The psychologist Jung first identified introversion and extraversion and described psychological types in great detail. The interior life — which draws a person to the hermit life — is a complex but definite influence on me, fed by intellectual sources. As an adolescent, already something of a solitary, I suffered a brain tumor and surgery that resulted in a year out of school that convinced me to pursue a life of learning and reflection. I suppose my hermit interests began there, too.

I mention in the book that I am not trying to promote or popularize hermits.

Hermits seem to be a neglected social phenomenon. More importantly, the website and book arose because it occurred to me that just as historical hermits were more than eccentric recluses and solitaries but in fact could serve as models of ethics, aesthetics, and personality, so it seemed to me that others could benefit from learning of their history, their sayings, their wisdom.

At the outset of starting Hermitary I found old books and stray bits of information about hermits, especially from particular religious points of view. Bringing these bits of knowledge together convinced me to share what I learned, anonymously. I do think hermits would rather stay out of the limelight, while telling their stories nevertheless, if only as catharsis. Hermits reflect universal sentiments and emotions, and chronicling the universality of their history can tell us a lot about ourselves.

I am content with the guise of amateur historian, little philosopher, and frankly, old librarian, neither scholar nor journalist. I did not leave my dwelling place to discover all of the information in Hermitary and The Book of Hermits. So much is past history, so much has been documented. Yet there is always something new. I just wanted to put it together in one place.

Tom Neale spent a total of fourteen years alone on a little island in the Suwarrow Atoll in the South Pacific, where he found peace and happiness in solitude. We have a look at this extraordinary life.

If we return to the original sense of what philosophy means, “love of wisdom,” then the historical hermits pursue this project, this search for wisdom, with their entire lives, not abstractly but entirely. As Kahlil Gibran put it, “A hermit is one who renounces the world of fragments that he may enjoy the world wholly and without interruption.” This is what we see in the historical hermits. At the same time many hermits were writers and poets, many were the subjects of biography or hagiography, so we actually have a good sense of how the hermits were lovers of wisdom.

Interestingly, while hermits did live in caves and forests, at the same time they interacted with others as they preferred. Hermits are not recluses fearing or distrusting others. Eccentric, perhaps, but not pathological! Potential hermits know that they must — as someone once wrote — check in their baggage before pursuing the hermit life.

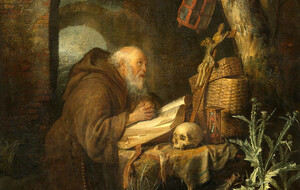

What is fascinating about hermits is their universality. From ancient to modern India, China, Japan, to early Christian desert hermits, throughout Eastern and Western Europe from the Middle Ages to more recently. Hermits span history, geography, culture, and tradition. Their motives are psychological, ethical, aesthetic, from a love of nature to a pursuit of the spiritual to a desire for solitude and simplicity. It is a journey I enjoy chronicling in the book.

In short, the confrontation with modernity. In the West, hermits were always hounded by the institutional church, which wanted hermits carefully controlled and supervised in monasteries. The first desert hermits in ancient Christian Egypt were monks fleeing the urban monasteries. They were not heretics but objected to the rote formulaic rituals and practices of the church that stultified true spirituality, simplicity, asceticism, and authentic self-sufficiency — in short, pursuit of a life of wisdom. The hermits fled not only the world but the church in the world, as Thomas Merton put it.

My favorite model is Paul of Thebes, who asked a visitor to his desert cave, “How fares the world these days? What empire holds sway? Are the people still misled by demons?” Of course we can secularize and update the vocabulary, but it is still a valid sentiment, a quintessential hermit sentiment.

The same contention happens in the Middle Ages. When new religious orders emerge, based on the desert model of individual cells for hermits and a common area for Sunday ritual and socializing, the new orders are opposed by the institutional church. The archetypal theologian Thomas Aquinas expressed skepticism about eremitism, agreeing with Aristotle that a solitary is either godly (which is impossible) or a beast.

With modernity come economic and social changes, skepticism and religious wars. Hermits were suppressed. But a new form of expression emerged: solitude.

Yes. The hermits had designed the life and project, but with social, economic, and political changes, the lifestyle collapsed under overwhelming pressure. Solitude, a secular and individual phenomenon, emerges. Solitude reflects a condition, not a project. Nevertheless, solitude is itself a philosophical reflection on conditions of life as much as a response to life. The sense of solitude always lurked beneath the eremitic project. The Book of Hermits devotes a lot of space to solitude.

The ancient Greek thinkers Diogenes and Epicurus were trying to craft a way in which the individual could eschew corrupt society without overt confrontation. Thus Diogenes was considered mad because he was homeless, unconventional, but spoke truthfully, even to the face of Alexander the Great.

Ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus (341-270 BC) believes that the way to ensure happiness throughout life is to reduce one’s desires so that they can be easily fulfilled.

Epicurus saw small private personal pursuits as the best course of life for the intelligent person, and this necessitated solitude. Seneca devised a Stoicism that bolstered an ethic for the solitary life. By the time of the Renaissance, with disparate figures such as the poet Petrarch, the essayist Montaigne, the philosophers Descartes and Pascal, culminating in the early modern period with Rousseau, solitude is the refuge of what in another era would have been eremitism. But then, what is the difference between them and the “hermit in the city” of the ancient Chinese Taoists?

Solitude as a theme in literature and art accelerates in interest among the well-read. By the nineteenth century, philosophers of solitude pick up on the implications of this project to make life meaningful, autonomous, and content. Here the list of thinkers is long and requires careful teasing-out of the solitude theme.

In the nineteenth century, Kierkegaard, Schopenhauer, Dostoyevsky, and Nietzsche (who expands wonderfully on the figure of Diogenes in his parable of the madman in The Gay Science); in the arts are Romantic poets from Lamartine and Vigny to Hölderlin and Wordsworth, from Emily Dickinson, to tales about “isolatoes” in Melville and Conrad. More eclectic philosophers of solitude include Emerson and Thoreau. And, of course, by the twentieth century, we find solitude themes of alienation and existentialism in Kafka, Rilke, Hesse, Pessoa, Camus, Heidegger, Simone Weil, Gibran, and Ionesco, to mention just a few. I give all of these figures their due in the book. The rehabilitation of hermits in the twentieth century is a grand project: the reconstruction of lost values and the philosophical insights of the historical hermits.

DP: But then, we also have the modern phenomena of loneliness and social isolation, which can look similar to solitude and perhaps be confused with it. For example, in modern Japanese culture, we have the phenomenon of the hikikomori — young people who live socially reclusive lives by choice. Wikipedia sees them as a kind of hermit.

Would you agree that every kind of voluntary social isolation is an instance of eremitism, or do hermits need to have some “loftier” goal, for example to see their eremitism as a spiritual exercise, a means to achieve some particular mental state that is valuable in itself?

Many solitaries would be reduced by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) of the American Psychiatric Association to a “personality disorder.” The DSM even has a “cluster” labeled “odd and eccentric” behavior, with its behaviors labeled on a trajectory of psychopathy and deviance culminating in crime, violence, and remorselessness. To be sure, this is not the hikikomori.

Solitude as a psychologically oppressive phenomenon has characterized social alienation in modernity for at least the last two centuries. Social withdrawal such as hikikomori, what researchers recently call “a culture-bound syndrome of social withdrawal,” is the product of anxiety and dissociative disorders prompted in part by modernity — society, technology, culture, exactly what historical hermits consciously avoid.

Robert Rodriguez: The Book of Hermits. Here is a new, comprehensive book on Hermits by Robert Rodriguez, the creator of the hermitary.com website. This is a wonderful, sympathetic and informative book from a lifelong researcher of hermit life and lore. I loved reading it, and I cannot recommend it more. Get it right here on Amazon! - Dr Andreas Matthias, Editor of Daily Philosophy.

Amazon affiliate link. If you buy through this link, Daily Philosophy will get a small commission at no cost to you. Thanks!

Eremitism is, indeed, a voluntary social withdrawal, with emphasis on the volitional motive. One does look for some loftier goal, some conscious design or project, that distinguishes eremitism. In the historical hermits, this pursuit is marked by an application or discipline that is constructive, ethical, self-reliant, creative, and — as you rightly suggest — a spiritual exercise, a project of transcendence.

DP: I just read a Guardian article about “River Dave,” a hermit who is now, in old age, abandoning his hermit life.

It surprised me that he said in this interview that he might have been mistaken when he chose to live as a hermit: “Maybe the things I’ve been trying to avoid are the things that I really need in life … I grew up never being hugged or kissed, or any close contact.”

And in the video he adds: “Maybe I was a hermit for nothing.”

This is a sobering summary of a hermit’s life. Apart from that particular person, whose personal circumstances we don’t want to judge, what does this tell us, in your opinion, about the different kinds of hermits? Can someone who judges that his hermit life might have been “for nothing” be called a “genuine” (i.e. spiritual) hermit? Can we really imagine that a whole life lived as a hermit might have been “for nothing”? Is someone who judges their life like that mistaken in their judgement?

Isn’t it inevitable that a life lived in isolation and concentration will bestow some kind of gain on a person, in terms of valuable insights or a clarity of mind that they wouldn’t have had otherwise? And yet, this particular hermit does not seem to see it like that. And this leads us to a more general (and unsettling) question: how much of the hermit movement might just be people who leave society for the “wrong” reasons, because of some kind of trauma, rather than in a positive search for a better, more spiritual alternative? Or shouldn’t we talk of “wrong” and “right” reasons for being a hermit?

You are right that motive matters, especially among secular hermits, who fall back on personality as an eremitic motive. The rediscovery by Chinese youth of their nation’s historical hermits is a constructive and balanced view of eremitism and its reconfiguration today, getting beyond just personality.

In the case of “River Dave,” however, the psychology is not inexplicable. He squatted for years on another’s property and feared disclosure. Upon discovery comes shock, intense anger, resentment of others not suffering his fate, and denial of his motive, doubting and betraying his own long-held motives. He is jailed for trespass and vows he will die there, a deep despair. But he is let out, forced to redefine his life. Dave begins telling his story. Suddenly, acquaintances reach out to help him, and even strangers he may have once disdained contribute to a GoFundMe campaign, of all things. Out of despair and rejection of his past may yet emerge meaning, a new plan. Dave denied the worth of his hermit life in order to salvage his self-image, that life which had been taken from him. Notice that these are the classic — need I say inevitable — Kubler-Ross stages of grief. Secular hermits, cutting off spiritual resources, risk vulnerability deeper than their historical counterparts. By no means does the secular exclude spiritual, philosophical, aesthetic, or ethical resilience. I mention the various fates of several modern secular hermits in the book.

So little time and such an enormous topic!

Hermits are at the core of Asian cultures. India’s asramas or social stages, culminate with retirement to the life of a forest hermit as a householder’s highest aspiration, a further option being the wanderer or sadhu. A favorite Buddhist Pali text of this era is titled “Wander Alone Like the Rhinoceros.”

In ancient China, hermits represent the highest ethical standard. In the legend of the Boyi brothers, who reclused to the mountains rather than serve their father, lord of the province, in attacking and overthrowing a neighboring province, we have a strong moral decision that inspires the high ethics of a whole culture, beginning with Confucius, who spends his life trying (not very successfully) to inculcate ethics into the many provincial lords, along with a scheme of education, ritual, hierarchy, and the arts.

One anecdote describes a journey of Confucius to a province, with an attendant of Confucius alighting from the carriage to consult farmers in a field about directions. The attendant speaks of his master but the farmer replies that a true master would know the difference between one grain seed and another. The farmers continue: Why are you pursuing lords, vainly hoping to reform the world? Better to flee the world. The attendant returns to Confucius and reports the exchange. Confucius replies, “They are hermits.”

For Confucius, one’s personal loyalties to family, friends, co-workers and superiors are more important than the rules of some abstract ethical theory. This has been called the “particularism” of Confucian ethics.

Eventually, the Confucian doctrine became “Serve the lord when he is good; if he is evil, recluse.” This is the hermit guide for the later Taoists and Buddhists, for over a thousand years, with hundreds of officials at court reclusing to distant villages, farms, and mountains rather than remaining at court. Because they include many poets, from Tao Chien to Du Fu to Hanshan to Shiwu (Stonehouse), we have a significant corpus of eremitic literature and documentation. The same phenomenon applies to Japan, where Zen Buddhism and a tradition of reclusion generates hermit-poets from medieval to modern, such as Kamo no Chōmei, Saigyō, Bashō (the master of haiku poetry and aesthetic theory of wabi and sabi), and Ryōkan.

Solitude is a component of practice in modern India even if not the goal, as in the philosophical thought of Hindu figures including Ramakrishna, Aurobindo, and Ramana Maharshi. A formal philosopher who clearly discerns the core implications of solitude for the individual is J. Krishnamurti.

So we have lightly brushed some of the many sources of eremitic thought! If philosophy is both the love of wisdom and the pursuit of a life of wisdom, then the hermits are among history’s best models.

Being a hermit is essentially the same across cultures. All the hermits share the same disposition, tap the same sense of simplicity, share the same goal of harmony of self with nature, and pursue the love of wisdom in remarkably similar ways. Of course, we encounter the inevitable issue pointed out by Krishnamurti, that the hermit in solitary meditation is still a Hindu hermit or a Christian hermit, etc. So the hermit is transcending not culture as such but lack of self-consciousness. Pursuing the lives and sayings of the historical hermits reveals this path toward love of wisdom.

The book falls between scholarship and reportage. I delve into a lot of names, many familiar in philosophy, religion, or world literature, many perhaps not, ironically, to fields like history or biography. Nor have these many figures been approached in terms of solitude in their thought, and placed in this context. In many respects, the book’s approach is academic but I am not a scholar; the intended audience is the intelligent but especially the curious reader. I tried to be thorough, as we’ve been describing here, following up hermits, eremitism, and solitude themes. The book culminates with modern hermits and solitaries, both men and women, all the way up to today. I add an appendix on the intriguing role of the dwelling-place in the lives of the historical and modern hermits.

We saw how, for Heidegger, we let things be what they are through experiencing them in the full compass of their relations to nature, human life, and the ‘holy’ and mysterious. Chōmei, steeped in the Buddhist conception of the interdependence of everything, would concur.

As I mentioned, I started with the Hermitary website, back in 2002. That project has been ongoing, helping consolidate all I learned and found interesting along the way. The site complements the book. I run a blog that updates hermits today and another with my reflections on related topics. I am building web galleries featuring hermits in art, photos, film, video, and music. New insights? I enjoy discovering the presence and influence of eremitism, subtle or obvious, in every field of human expression: art, literature, society, psychology, and culture. The book is stuffed with everything hermit!

Robert Rodriguez’ “The Book of Hermits” is a work of impressive scholarship, covering the global history and lore of eremitism from antiquity to the present.

The book is available for pre-sale from the usual vendors. I update a list of vendors on the hermitary website. An ebook version of the paperback is also available.

Oh, there are so many! Here is one. I like the sentiment of the early twentieth-century writer T. F. Powys, author of Soliloquies of a Hermit, who wrote that mystics should give up their metaphysical speculations and content themselves to “peacefully planting cabbages.” And I highly recommend the little animation of Jean Giono’s “The Man Who Planted Trees” for a portrait of what a modern hermit might look like.

◊ ◊ ◊

Do you still have questions about hermits? Put them in the comments below and I will relay them to the author. Have you tried the hermit life or a life in solitude yourself? Tell us about your experiences in the comments!

Cover image on this page by Tengyart on Unsplash .