Going Slow

A rhetoric of slowness and speed has been used by philosophers since the ancient periods to characterise and assess different ways of life. Buddhist, Confucian, and Daoist discourses exploit associations, literal and figurative, between slower styles of life and virtue, on the one hand, and hastier styles of life and vice, on the other. Kongzi (Confucius) praised the virtue of ‘timeliness’, which manifests in an ability to ‘advance when it is appropriate to advance and remain still when it is appropriate to remain still’. A timely person acts and speaks in thoughtful, considerate, considered ways, guided by the ‘rituals’ central to Confucian life.

Early Daoists texts, too, use speed and slowness as moral metaphors. Zhuangzi laments the ‘sadness’ of harried, overcommitted people whose lives are like ‘a horse galloping by, unstoppable’, always active, ‘exhausted to the point of collapse’. The unknown authors of the Daodejing diagnose this hastiness as a sign one has been swept away by drives to be ‘busy’ — a turbulent condition all-too-obvious in agitated Confucians, ‘regulated and confined by [their] own schemes’. Racing headlong through life is a sign we have ‘lost the Way’. The more one takes on, the faster one has to go, darting about, frantic to satisfy the duties, demands, and expectations of a corrupt social world from which the wise person retreats.

The Buddha, too, laments the distracting effects of the attachments and cravings of the lives of ‘unenlightened worldlings’. The Dhammapada says that ‘misguided’ people ‘strongly rush towards pleasurable objects’, swept away in an unceasing ‘flood of passionate thoughts’. In an Udana story, the Buddha compares them to moths flying into flames — ‘Rushing headlong, missing what’s essential’, the bugs keep ‘meeting their misfortune’, unable to recognise the self-destructiveness of their actions. Their frenetic activity offers a perfect image for the restless insatiability of worldly life:

Only causing ever newer bonds to grow.

So obsessed are some by what is seen and heard,

They fly just like these moths — straight into the flames.

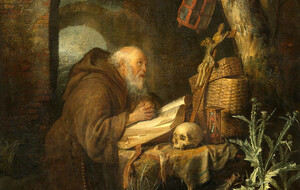

By contrast, the lives of Buddhist monks and nuns are characterised by a deliberate slowness, literally and figuratively. Without giving into torpor and enervation, a monk or nun is ‘constantly scrupulous, cautious, observant’, an array of virtues shown in quietist stillness. The point is not to grind to a halt: the Vitakkasanthana Sutta warns that ‘slowing down’ shouldn’t be a prelude to dull passivity. Instead, the Buddha’s point — as for Kongzi and Zhuangzi — is that our relation to virtues and vices are aptly described by the metaphors of slowness and speed.

The connections between slowness and speed, virtue and vice, are rarely explored in contemporary philosophical literature. It does, however, feature in some recent popular books that use the metaphor of slowness and speed, ones that make some very large moral claims about the danger of speed and the moral importance of slowing down.

A comprehensive overview of Erich Fromm’s philosophy of happiness. We discuss his life, his ideas and his main works, both in their historical context and how they are still relevant for us today.

Slow and Fast

In the early 1990s, a community of Italian farmers and gastronomic activists, concerned about the erosion of traditional food cultures, started what later became the Slow Food movement. Alarmed at modern agricultural practices and the deterioration of the quality of food and food cultures, the Slow Food movement sought out alternatives. By revitalising traditional farming styles and culinary cultural practices, they worked to create ways of relating to and appreciating food marked by appreciativeness, cooperativeness, respect for tradition, and environmental sustainability. Practically, the emphasis was on preserving local culinary traditions, teaching gardening skills, programs for ‘taste education’, campaigns against fast food, and cultivating meaningful relationships with producers and the land.

Photo by Kamala Saraswathi on Unsplash

Accompanying this, though, are claims about the moral dimensions of the ethos of slowness. For Carlo Petrini, founder of the International Slow Food Movement, slowness is ‘a new moral imperative’. Quite what this means will depend on who one reads. For Luigi Veronelli, the erudite viniculturalist — he translated de Sade into Italian — slowness is a means of reconnecting deeply with one’s natural and cultural heritage. True to his aphorism, ‘the tinier the vineyard, the more perfect the wine’, Veronelli’s theme was the intimacy of nature and culture. Understanding their interrelations requires us to ‘walk the land’, something that takes time, patience, and leisurely immersion in inherited traditions and cultures of food. Slowness, for Petrini, ‘unites the pleasure of food with responsibility, sustainability, and harmony with nature’.

Such language intimates something of the ‘moral imperative’ emphasised by Petrini and shared by the enthusiasts who later developed Slowness into a comprehensive moral, political, and cultural movement. We can nowadays read about and practice Slow Cinema, Slow Science, Slow Sex, and much else. Some of this enthusiasm reflects a politicised sense that Slow is a subversive ethos in a capitalist, consumerist world dominated by fastness, productivity, and machination. The original Slow Food advocates would applaud. Petrini was a socialist activist who came to fame campaigning against MacDonalds, while Veronelli was a socialist and anarchist, one-time student of the liberal political philosopher, Bendetto Croce. Slowness, for them, aligns with wider activist efforts set against the destructiveness, violence, and relentlessness of modern cultures.

Perhaps the fullest statement of the moral ethos of Slow is the Canadian journalist Carl Honore’s bestseller, In Praise of Slow.

‘We are all enslaved by speed’, he declares, trapped by imperatives to become ever-faster and ever-more productive. Driven to the extremes of our tolerances, speed ‘strikes at the heart of what it is to be human’. It is the dominant driver of the worst features of the modern world: the wastefulness of fast food and fashion, the violent exploitation of nature, the harsh demands and pace of work life, and the erosion of our interpersonal relationships. Everything must be more and be done faster, an unsustainable tread-mill of busy self-destruction justified by thinly defined values, like efficiency, innovation, and productivity.

Without radical action, warns Honore, speed will destroy bodies, minds, and natural places and their inhabitants, accelerating our ‘enslavement’ and dehumanisation. Consequently, like all disciples of slowness, Honore offers proposals for challenging cultures of speed. Some involve social and political activism, like supporting trade unions and environmental groups working to create slower, more sustainable ways of working and engaging with nature. Others have a more personal dimension. Honore encourages ‘diverse acts of deceleration’, emptying our cluttered schedules to make time for ‘activities that defy acceleration, like meditation or gardening or yoga’.

Photo by Dan Dumitriu on Unsplash

Lutz Koepnick’s book On Slowness also speaks of developing ‘strategies of hesitation, delay, and deceleration’. In my local bookstore, the books with ‘Slow’ in their titles are stacked alongside ones devoted to ‘Silence’, ‘Stillness’, and ‘Quiet’. Their authors connect slowness and stillness with other staples of the modern self-help and spirituality literatures: a revivified sense of the beauty and wonder of nature, ‘finding peace and purpose in a hectic world’, the ‘pleasure and value [of] a simpler life’, and ‘bringing calm to a busy world’.

I sympathise with criticisms of cultures of speed and share many of the concerns informing an ethos of slowness. I also agree that slowness contains the ‘moral imperative’ perceived, if not elaborated, by Petrini. But arguably they do not fully identify the exact nature of that ethos.

Consider, for instance, Honore’s appeal for ‘acts of deceleration’, like the effort to make time for ‘activities that defy acceleration’, like meditating and yoga — the two other omnipresent topics of modern self-help and spirituality literature. Punctuating the working day with a walk across campus, pausing for a moment to enjoy birdsong, starting the day with tai chi rather than with email … all of these are strategies of slowness. But there are two problems.

First, ‘slowness’ and ‘speed’, as characterised by Honore, get locked into an unhelpful dualism. A complicated set of qualities that relate in all manner of complicated and contextually sensitive ways get artificially divided into two groups:

This is too polarised to capture the complexity of our practices and their own distinctive paces and rhythms. ‘Fast’ and ‘slow’ do not pair off that neatly with those qualities. Aggressiveness can be very effective if one speaks calmly and acts slowly — the agitated, shouty lout of popular stereotype is only one kind of aggression. A lawyer can be simultaneously fast and analytical, a teacher can be busy and calm, so matters are more complicated. Granted, one can overemphasise some of these qualities — it used to be the fashion for certain philosophers to celebrate speed, aggression, and rapid reactions to the poor soul presenting their ideas for consideration at conferences and seminars.

A second problem is that walking, gardening, and other ‘slower’ activities are not immune to the imperatives of speed. I could do all those things but in a physically and psychologically ‘fast’ way. Clock-watching and impatience can be constant companions during ‘chill-out’ time, corrupting the ‘quality time’ devoted to reading a novel or working in the garden. A culture of speed easily leaks into these activities and accelerates them.

After all, it is easy to experience one’s leisure activities under the categories of efficiency, productivity, output, competitiveness, beating one’s previous record. Acts of deceleration only really work for a person willing and able to decelerate. Hurried people impatiently demand quick fixes and easily digestible moral recipes — tellingly, Honore’s later books include The Slow Fix and 30 Days To Slow.

Honore does, however, reject another sort of polarisation. A summons to slowness should not take the form of a total abdication of speed. The call is not to slam on the brakes and take one’s foot off the accelerator altogether, but rather to restore appreciation of slow styles of life and thought in a social world that increasingly seems to be all accelerators and no brakes. In life as on the road, too slow can be just as bad as too fast and there is little wisdom in careering from one extreme to the other:

As the literary scholars, Maggie Berg and Barbara Seeber nicely put it in their lively polemic The Slow Professor, slowness should not be a ‘counter-cultural retreat from everyday life’, nor a ‘slow-motion version of life’, nor the latest cunning ploy by our bosses to trick us into carrying on business-as-usual by other means. The difficult, delicate task is ensuring that the culture of speed does not dominate our overall outlook and conduct. As the Irish philosopher, Aine Mahon, says, our challenge — psychological, moral, and political — is to critically adapt to the pressures, incentives, and expectations that encourage ‘a privileging of the rapid’.

Photo by Pelargoniums for Europe on Unsplash

What we need, then, is an account of how one can ‘slow down’ and better resist the imperatives of speed — ideally, that account would also help to fill out Petrini’s talk of a ‘moral imperative’. Concerns about the exploitation of workers and the destruction of nature are genuinely important, but they do not fully explain out the full moral significance of ‘speed’ and ‘slowness’.

What did Honore mean when saying that submitting to speed ‘strikes at the heart of what it is to be human’? Why did Berg and Seeber announce that slowing down is ‘a matter of ethical import’ and warn that becoming a ‘disciple of speed’ should be ‘recognised as a form of self-harm’? Whatever is intended by such dramatic language, it goes beyond the sorts of concerns captured by moral concepts such as injustice, violence, and exploitation.

To get a fuller sense of what is morally at stake in slowness and speed, a good starting point is Honore’s advice that we ‘cultivate inner slowness’.

Inner slowness

Berg and Seeber warn that internalising the ‘psychology of speed’ tends to transform one’s attitudes, behaviour, and perspectives for the worst. Driven by a zeal for speed, rapidity, productivity, and achievement, one becomes ‘jealous, impatient, and rushed’, resistant to ‘allowing room for others and otherness’ and ‘the values of density, complexity, and ideas which resist fast consumption’. Complex matters cannot be rushed, and understanding often demands more time than is granted by the zealous ‘disciple of speed’.

For Berg and Seeber, such transformations are morally destructive, which is the deep concern shared by Kongzi, Zhuangzi, and the Buddha. All of them condemned the moral, physical, and psychological hazards of becoming this restless, relentless person who cuts corners and carves a destructive path through the world. What is missing from this, however, is a description of the distorting effects on one’s moral character. Internalising the imperatives of speed is corrupting insofar as it feeds a range of vices and failings while also simultaneously eroding our capacity for virtue. By corrupting our moral characters, cultures of Speed are morally significant and dehumanising — after all, moral virtue and excellence is one characteristically human attainment.

Aristotle’s theory of happiness rests on three concepts: (1) the virtues, which are good properties of one’s character that benefit oneself and others; (2) phronesis, which is the ability to employ the virtues to the right amount in any particular situation; and (3) eudaimonia, which is a life that is happy, successful and morally good, all at the same time. This month, we discuss how to actually go about living a life like that.

Celebrants of slowness — like Honore and Petrini or Berg and Seeber — do not much use the language of virtue and vice. It is clear, though, that they’re concerned about the distorted moral character of ‘disciples of speed’.

To see this, consider one of their ideological rivals, the early 20th century priest of speed, the Italian poet and art theorist, Filippo Tomasso Marinetti, founder of Futurism. In vivid dithyrambic prose, he urged us ‘to hymn the man at the steering-wheel’ and exult in the sight of ‘deep-chested locomotives … and sleek flight of planes’. In his 1909 Futurist Manifesto, a celebration of an ‘aesthetics of speed’, Marinetti also sketched the characteristics of a true accelerationist. Freed from their ‘old shackles’, the true man has a zealous ‘love of danger’, scorns ‘contemplative stillness’, and in all their actions work to ‘glorify aggressive action’. Forever in a state of ‘restive wakefulness’, they recognise that human life ’comes down to reproduction at any cost and to purposeless destruction’. Consequently, the high-octane Futurist disciple of speed finds a sustaining satisfaction in ‘a new beauty, the beauty of speed’.

The character described by Marinetti is aggressive, dangerous, impulsive, reckless, and refuses to be ‘shackled’ or slowed by concern for consequences or self-preservation. Considered as a kind of person, they are dominated and driven by a whole set of vices fuelled by a ‘psychology of speed’, so let’s call them accelerative vices. Berg and Seeber, interestingly, also characterise the disciple of speed as a corrupted sort of character. By internalising the values and imperatives of a culture of speed, for instance, our perception of people becomes jaundiced: one starts to feel frustrated at students, colleagues, and neighbours who ‘eat up’ or make ‘demands’ on our precious time, taking us away from whichever activities matter more to us.

True, protecting our time is sometimes necessary. Some people are time-wasting or boorish. A psychology of speed, though, pushes well beyond that reasonable protectiveness about one’s time. The disciple of speed is as a rule aggressive, dominative, impatient, and unaccommodating — willing to leave behind those who cannot keep up in the rat race. Berg and Seeber quote one ‘time management manual’ for academics which obnoxiously complains that they ‘waste a tremendous amount of time’ by doing such inessential things as ‘chit-chatting at the water cooler’. If unproductive activities really cannot be avoided, they can be reclaimed. One could, for instance, ‘sneak in reading … on the way to Aunt Joanie’s barbeque’.

Such behaviour may seem efficient and productive to a disciple of speed, but to those with a broader moral outlook, it smacks of a narrow selfishness and a myopic sense of what matters in life. A life dominated by the values of speed becomes too narrow, too rushed, too insensitive to the broader range of values integral to a well-rounded human life. Many things only really work when done slowly. A first date, caring for an aged relative, reading edifying books, walking through woodlands … all these require virtues of slowness. The philosopher, Michael Oakeshott, said a good conversation should enjoy a ‘genial flow’, neither stalled by ‘slow sententiousness’ nor rushed along in an ‘impatient cascade of words’.

Photo by Radek Grzybowski on Unsplash

We can now restate the moral concerns about cultures of speed and the moral imperative animating the ethos of slowness.

By internalising the psychology of speed, a person’s character and life will be at risk of becoming dominated by the imperatives, pressures, and values of the culture of speed. Speed, rapidity, productivity, efficiency, acceleration — these become central to our activities, projects, and relationships to other people. All of this puts pressure on our other values, like collegiality, careful appreciativeness, and amiable neighbourliness.

Moreover, it becomes ever-harder to exercise all of those virtues premised on slower styles of thought, feeling, and action — carefulness, diligence, reflectiveness, spontaneity, and thoughtfulness to name but a few. In their place arise the accelerative vices, like aggressiveness, fractiousness, impatience, superficiality, intolerance for whatever is slow or subtle, insensitivity to depth and complexity, and, above all, a myopic and self-centred vision of life. Worse, the corrupting effects of becoming a disciple of speed will be disguised within cultures that celebrate Promethean values — ambitiousness, productivity, achievement, busy-ness. Berg and Seeber discern this in areas of life ruled by ‘ideals of mastery, self-sufficient individualism, and rationalism’. In a worst-case scenario, dogmatic disciples of speed become utterly incapable of ‘inner slowness’.

I suggest that the dehumanising effects of cultures of speed should really be understood in terms of their corrupting ability to distort moral character. By emphasising character, one need not ignore the baleful effects of speed on mental and physical health, workloads, and the environment. What must be taken seriously, though, are the attitudes, dispositions, and outlooks that are working within disciples of speed. At the same time, taking seriously the corruption of character also helps us understand what it means to cultivate inner slowness. What someone corrupted by the imperatives of speed really needs is to silence and still all those drives and imperatives integral to what Mahon called the ‘privileging of rapidity’.

The moral imperative of slowing down therefore involves the curbing of our accelerative vices and the cultivation of the virtues of slowness occluded within modern cultures of speed. Everyone who writes about ‘fast’ and ‘slow’ emphasises that the modern world is dominated by ‘fast’ and hostile to ‘slow’.

Clearly, though, the dispositions to acceleration precede the emergence of modernity. The Daoist, Buddhist, and Confucian philosophers all condemned the accelerative vices — people ‘scurrying around’, endlessly busy, pursuing ever-more elaborate goals. Moreover, for all their differences, they extolled a similar set of ‘slow’ virtues, like moderation and reflectiveness. Indeed, they also agreed that moral self-transformation involved practices for ‘calming’, ‘restraining’, or ‘stilling’ our over-energetic attachments and cravings — ‘going slow’, one might say.

An obvious omission with this call to put a brake on the accelerative vices, resist the relentless imperative to speed, and cultivate inner slowness is that it requires some account of the proper pace of life. Without due context and standards, the injunction ‘Go slow!’ is just as useless as ‘Speed up!’ Honore, clarifying his denunciations of cultures of speed, points to a subtler account of the personal and cultural transformation central to the Slow Movement. Recall his point that we shouldn’t aim to ‘replace the cult of speed with the cult of slowness’, but to see to ‘do everything at the right speed’.

Photo by Lucas Alexander on Unsplash

What is needed is not just reiteration of the virtues of slowness and salutary cautions about fixation on speed. A flourishing life requires more than just a balanced account of the relevant excellences of character. It also needs what Kongzi called a sense of ‘timeliness’, a sense of the proper rhythm and timing of our actions and responses, something he derived from the array of ‘rites’ inherited from the Zhou Dynasty. In a musical metaphor, what is needed is a judicious ability to ‘perform’ our lives at a timely speed, one appropriate to the setting and ‘audience’. A good musician knows some pieces ought to be played slowly, others quickly, others in carefully constructed rhythms of alternating speed. Indeed, the musical metaphor is popular among Slowness enthusiasts. Berg and Seeber talk of appreciating the ‘rhythms’ of life and thought and the importance of being able, like a good jazz musician, to ‘give meaning’ to ‘periods of rest’, making discerning use of ‘pauses and periods that may seem unproductive’.

A good name for this attainment is what musicians call tempo giusto, the ability to achieve an ideal tempo. It requires a whole set of sensitivities and skills, each of them helping us comport ourselves according to criteria of sensitivity and appropriateness. A wise person uses this discerning sense of appropriateness to intelligently exercise their virtues — hence the timeliness of the Kongzi’s ‘consummate person’. This proper rhythm for one’s life may be provided by the Confucian rituals, Buddhist monastic discipline, or Daoist spontaneous responsiveness to ‘the ten thousand things’. For those without commitment to these dispensations, the task will be to construct their own substitutes. Whatever their own rhythms of life, they must grapple with the entrenched cultures of speed that constantly work to drive the extension of ‘fast’ into increasingly more areas of life.

The prospects for successfully cultivating the virtues of slowness through mastering a sense of tempo giusto will depend on the specific strategies of deceleration one attempts. The Confucians maintained that properly timely ways of living required a restoration of properly humane ritual structures, a claim attractive to those who want to slow down within the world while still remaining a part of it. By contrast, the Buddhists were reticent, favouring monastic ‘renunciation’ and a retreat from the pace and passions of worldly life. The Daoists did not go that far, despite their image as mountain-dwelling recluses, but they did insist that authenticity, humility, spontaneity, and the other virtues of someone ‘on the Way’ were only really possible if one tried to withdraw from mainstream human life. Zhuangzi, certainly, condemned the frenzied lives of his contemporaries, and his exemplars of authenticity, the zhenren, evince a ‘flow’ and ‘stability’ that mirrors the Way of Heaven.

For these ancient philosophers, as for modern champions of Slowness, an authentically flourishing human being shapes their life according to a proper sense of pace or rhythm. By doing so, their actions are timely, and ultimately characterised by an adaptability, agility, and responsiveness — like a musician shifting between allegro and largo as the piece requires. Like music, a human life cannot be properly performed at a single speed. In cultures of speed, like ours, ‘going slow’ will make sense for most people, but warnings about the corrupting effects of internalised psychologies of speed should not obscure the wisdom of timeliness.

For a wise person, a well-lived life should be lived tempo giusto — ‘Sometimes fast. Sometimes slow. Sometimes somewhere in between’.

◊ ◊ ◊

My thanks to the editor, Andreas Matthias, for the invitation to contribute, and to David E. Cooper for his comments on a draft.

Cover image by Pascal van de Vendel on Unsplash.